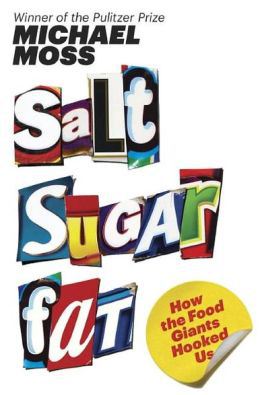

Michael Moss’s Sugar Fat Salt: How the Food Giants Hooked Us is an important book. A really important book. Keeping my ranting and ramblings down to a readable word count is going to be a Herculean task, so I will attempt to focus myself as such.

- Part 1: The book as a book

- Part 2: The information contained in said book

- Part 3: Why I wish I had read this book when I was 9 years old, even though it is 500 pages long and not part of the Babysitters Club Series, which means I never would have read it

Part I: The Book as a Book

It’s been a long time since I’ve read a good food-based nonfiction book. Ever since I first encountered Mr. Michael Pollan’s work, my American-Diet-Food-Mind was blown open and I was ready for all sorts of other food-books. Sugar Salt Fat serves the same function as Pollan’s (and others’) work: to help you, the consumer and eater, see food beyond the scope of your own dinner plate, and therefore see how outside cultures, longstanding mythology, and corporate interests are shaping the way you eat.

With a title like Sugar Salt Fat, I expected an examination of how each of these three ingredients ravage your body and contribute to the obesity epidemic and basically are ruining America. Not the case. Moss’s work is all business – the business of making and marketing processed foods, that is – and this book explores on how sugar, salt and fat affect the bottom line of giant food manufacturers like General Mills, Kraft, Coke, and many others. It’s a corporate expose, not a nutrition manual.

Moss’s book is hefty, but the chapters are short, the prose readable, and the stories intriguing. Each chapter reads like an article – complete within itself – but the secrets of corporate food culture were so alluring that I couldn’t put it down.

Part II: The Information Contained in Said Book

Like I said, this is a really important book – another food manifesto for the 21st century that I hope many, many people read.

This is going to be poorly worded, but Moss’s thesis is this:

You, the consumer, the every day eater, have been convinced that processed food – anything in a crinkly plastic bag and a list of ingredients longer than 1 – is food. But it’s probably not. Once these companies tamper with these foods to A) make them last on the shelf without disgusting you B) make them completely irresistible to the American palate, these foods have so much sugar, fat, and salt, that your body doesn’t know what to do with them anymore. These added ingredients are making you sick.

The second half of the thesis:

These giant food corporations are in such heavy competition for the inherently limited amount of “shelf space” and “stomach share” available, they have zero qualms about adding more, more, and more of these ingredients in order to make their products more irresistible than the junk of their competitors.

So there’s a lie – that the processed food you eat every day is good for your body – and then corporate disregard for how their main business strategy contributes directly to obesity and illness.

Mind. Blown.

Don’t worry, there are plenty of little tidbits I’m not revealing here – the habits of food company CEOs, how Dr. Pepper became Dr. Pepper, why the fad school-lunch du jour of my elementary years – the Lunchable – was a significant “culinary” and marketing achievement for shoving processed foods down the throats of children…

I’m not bitter, I promise.

Part III: Why I Wish I’d Read This Book When I was 9-Years-Old

Oh wait, yes I am. I am bitter because I was a normal-sized little girl when I was a nine year old, a ten year old. I was taller than almost everyone in my class, though, so when we all had to stand on a scale in the nurse’s office in front of our classmates, I knew that I weighed more than almost everyone in my class. Certainly all the girls.

That wasn’t good knowledge to have as a little girl, but that’s not why I’m bitter. I’m bitter because around that same time, I remember a Saturday morning when I first felt shame about food. A box of Dunkin’ Donuts on the table, and I knew it was okay to eat 2 donuts. But the third donut, I probably shouldn’t have eaten. At the third donut I started making promises to myself, that I would never eat more than two again, that I shouldn’t have any snacks for the rest of the day, that I would maybe just stop eating donuts forever.

With the fourth donut came the self loathing. It was an awful feeling, to keep eating after I’d decided with my little-girl brain that I’d already crossed the line. And although I am not pinning my personal issues those box of fateful donuts, it was, in part, an awful feeling because these donuts were so delicious that I couldn’t say no. I wasn’t strong enough to resist. Good girls had more willpower – I must not be good.

It pisses me off to know that some middle aged men are sitting in laboratories, chemically engineering donuts to hit that “bliss point,” the point where your tastebuds take over, where you can’t say no – designing foods so insidiously so little girls can have breakfast and when they are done hate themselves and their bodies for years and years and years. I can’t help but wonder what effect a childhood grown on whole, unprocessed foods might have on eating disorders, food issues, the general female-body condition.

So read this book and then go to the market, cook yourself some dinner, give your kid a carrot, or whatever else you can do to step outside of the Corporate Food Cycle. If you don’t have time to read this book, read this article – it hits a lot of the high points. Please and thanks.