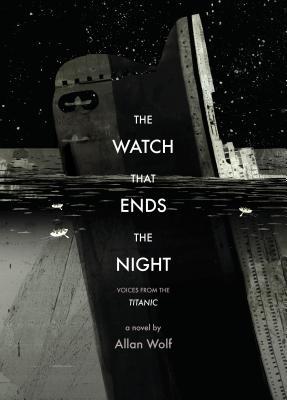

Back in June, Deborah Hopkinson’s Titanic: Voices from the Disaster lit a Titanic-related fire underneath me – I think the day I finished, I picked up Allan Wolf’s The Watch that Ends the Night: Voices from the Titanic.

(I probably also put the movie on hold at the library, but forgive me – as established, I was 12 in 1997)

The Watch that Ends the Night is the story of the Titanic told in poems, with different passengers, crew members, and others providing unique voices and styles to each verse. I am not always a fan of books told with poetry, but I loved both Wolf’s writing and story execution – the alternating voices were engaging, the variations in each poem’s style and form was subtle, and the poems stand alone. It’s the kind of writing that makes you want to slow down, maybe read aloud.

I’m glad that I read Hopkinson’s book first – although Wolf’s work is most certainly a work of fiction, the voices and characters are actual Titanic passengers, many of whom are profiled in Hopkinson’s work. I liked recognizing some of the more obscure characters who played major roles on-ship and during the wreck – the tireless and cheerful wireless operator, Harold McBride, was one of my favorite characters in both Hopkinson & Wolf’s works. But maybe even more interesting is when Wolf give some of the more famous characters an unlikely voice or point of view; his treatment of John Jacob Astor IV, the richest passenger on board, traveling with his pregnant 18-year-old mistress, was particularly unique and moving.

But the most enigmatic, surprising character with the most intoxicatingly rhythmic style? The Iceberg. Gimmicky? Eye-roll-inducing? No. Wolf’s Iceberg is dark, menacing, and constant, providing a voice for the undercurrent of pain, of destruction, of death that is so frightening about Titanic’s story… and about all stories. Nature always wins.

Overall, I was impressed by how Wolf uses language and style to capture these bigger, human themes. This book never feels like a “fictionalization,” but more like an exploration, using poetry to do things that straight nonfiction can’t. I’m not sure this is a book I could ever bear to read again, but I don’t think I will soon forget it.